8. Combat

8.1 General Rule

Combat occurs after all movement. Combat must be declared in

every location on the board where opposing pieces appear together.

These declarations are made one at a time by the phasing player, with

combat resolved immediately following each declaration. Combat

will be a battle or a siege, the latter if either of the forces is inside

a castle. After combat is resolved in a location, a new location is

selected, until all such locations are resolved.

8.2 Battles

8.2.1 Battle Procedure

Combat is resolved as a battle if neither force is inside a castle.

Deployments (8.2.2) produce Impact (8.3). The side with the higher

Impact is winning the battle. All blocks involved in a battle remain

concealed until deployed. After the battle is concluded, revealed

blocks again become concealed.

The Active Player (the attacker) starts the battle by making the first

deployment. Next the defender can respond (see Initiative 8.5).

When the battle stops, the side which has delivered the most

Impact will be the winner.

A tie in Impact favors the defender.

8.2.2 Cards and Deployment

Cards are used to deploy blocks into battle. Each card can deploy

one block. The card used to deploy a block must have the same

mon as the block. Cards and blocks with different mon cannot be

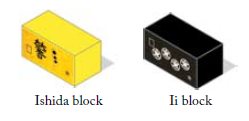

played together. Exception: Cards of all daimyo designations may

be matched to the sole Ishida block and the sole Ii block. As a reminder,

these blocks both feature a card-shaped rectangle in the lower right corner.

No card may be played,

nor block deployed, twice

in the same battle.

8.2.3 Deployment Procedure

The active player plays a card face up, and selects a block from

among his undeployed forces whose mon matches the card. The

block is indicated by placing it face up next to the main stack of

blocks. The card is placed face up on the active player’s side of the

board. The player counts the Impact of the deployment and adds

it to their total Impact on the Impact Track.

8.2.4 Initial Deployment

A leader block deploys without playing a card if no deployments

have yet been made with a card by that side in the present combat.

Leaders who deploy without a card are immune from Loyalty

Challenge (see 8.6).

Note: You can keep deploying leaders without a card until you deploy

your first block with a card.

8.3 Impact

8.3.1 Impact in general

Effectiveness in combat is measured in Impact. Impact is recorded

on the Impact Track using small cubes. Each side tracks their cumulative

Impact separately.

8.3.2 Base Impact

The base Impact of a deployment is the number of mon on the

block. This can be from one to four.

8.3.3 Impact Bonus

Add one point of Impact for each block of the same daimyo already

deployed (on the same side) in the present battle.

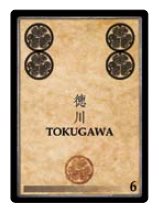

EXAMPLE: A player would score four Impact if he deployed a 2-mon

Tokugawa block into a battle in which he had previously deployed two

other Tokugawa blocks (the number of mon on the previously deployed

blocks has no effect).

8.4 Special Attacks

8.4.1 Cavalry and Gun Impact

Cards with a sword in the corner enable a Special Attack. When

used to deploy a block with a cavalry or gun symbol, an attack of

that type is launched. In a cavalry or gun attack, add two points of

Impact for the cavalry or gun, and another two points of Impact

for each block featuring that type of attack already deployed on the

same side in the present battle. If a cavalry or gun block is deployed

without a Special Attack card, do not count cavalry or gun points

towards its Impact.

8.4.2 Double Cards

Double cards feature two identical mon

in each corner. Double cards allow the

deployment of one or two blocks, both

of which must match the mon of the

card. The blocks are deployed one after

the other. (The second block can thus

gain a +1 Impact Bonus for matching

the daimyo of the first.) Neither of the

blocks so deployed can initiate a Special

Attack. A double card used to deploy a

block that can match to any card (Ishida

and Ii blocks) loses its ability to deploy a second block.

8.5 Initiative

Initiative rests with whichever side is losing the battle (has the lower

Impact score). That player has the opportunity to deploy blocks

one after the other in order to take the lead. Once he does take

the lead, initiative reverts to the other player. Since ties favor the

defender, the defender can take the lead by matching the attacker's

Impact. Initiative is passed back and forth between the players until

one player, who holds the initiative at the time, declares that he

will deploy no more blocks. When that happens initiative shifts

permanently to the other player, who may deploy as many more

blocks as he wishes and is able. When that player also declares he

is finished, the battle ends.

Once a player declares he is finished deploying, he cannot resume

deployments later in the battle. He may still play Loyalty Challenge

cards (8.6) against the other player’s deployments.

8.6 Loyalty Challenge cards

8.6.1 Procedure

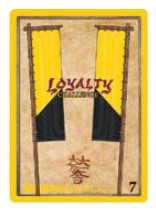

Loyalty Challenge cards are marked with

a nobori (banner). They are played out

of turn, immediately after a deployment

by the opposing player, to challenge the

loyalty of the block thus deployed. If the

deploying player can show from their

hand another card capable of deploying

the block just deployed, the block

remains loyal. The card shown to refute

a Loyalty Challenge returns to the hand

of the player that showed it. (The Loyalty

Challenge card remains played.) If the

deploying player cannot produce such a card, the block turns sides,

aligning instead with the player who played the Loyalty Challenge.

Move the block to the challenger’s side of the battle. Count Impact

for the block on the challenger’s Impact table. When the battle

ends, they revert to the former owner.

8.6.2 Loyalty and Special Attacks

Blocks which switch sides do not execute a Special Attack (8.4) at

the moment of their betrayal (even if indicated on the deploying

card) but can later contribute to Special Attacks for the side to

which they gave their loyalty.

8.6.3 Loyalty and Double Cards

A Loyalty Challenge card may be used to challenge the use of a

double card. Only one additional card must be displayed to refute

the challenge, even if two blocks deployed. If the challenge is successful,

both blocks defect to the challenging side. The Impact bonus

(+1 Impact for matching the mon of the first block) enjoyed by the

second such block is still counted.

8.7 Losses

8.7.1 How to Determine Losses

After a battle both sides take losses according to the Impact delivered

against them. Both sides lose one block for every 7 Impact

delivered by their opponent (always round Impact down). The losing

side in a battle loses one additional block.

EXAMPLE: A player wins the battle and had 5 Impact delivered

against him—he would lose no blocks. His opponent, who lost the battle,

had 9 Impact delivered against him—he would lose two blocks.

NOTE: Retreating forces are not overrun prior to making their retreat,

but an overrun can occur after the retreat (8.5.5).

8.7.2 Selecting Losses

The attacker suffers damage first, then the defender. Players select

which of their own blocks to lose. First must be selected any blocks

which defected to his opponent, then any other blocks which

deployed, then any blocks which did not. The identity of the lost

blocks is revealed.

8.7.3 Effects of Losses

Blocks lost in combat are removed from the map and

never return

to play

. Keep defeated blocks on the side of the board, visible to

both players.

8.8 Retreats

8.8.1 Retreats in General

The loser must retreat their remaining force to a single adjacent

location contiguous by road to the site of the battle (or castle

[8.8.4]). There is no limit to the size of a force which can move

together in retreat.

8.8.2 When the Attacker Retreats

The attacker must retreat to a location from which some of their

forces entered the battle (potentially a castle, but not an Off Map

Box) or if that is impossible to any other location. The attacker can

never retreat to the Recruitment Box or the Mōri Box (9.3).

8.8.3 When the Defender Retreats

The defender retreats, if possible, to a location containing no enemy

units, and from which the enemy did not enter the combat location.

If there is no such location, the defender may retreat to any other

adjacent location contiguous by road—including a location from

which the attacker entered the battle and/or a location containing

enemy blocks (8.8.5).

8.8.4 Retreats into a Castle

A castle can harbor retreating units, if the battle took place in a

location with a castle. A castle is a valid retreat destination only for

that side which controlled the castle prior to combat. If a castle is a

valid retreat destination, the retreating player may leave up to two

blocks in it. If there are more blocks remaining, these must retreat

elsewhere, as a group.

8.8.5 Retreats into Combat

It is possible for a retreat to cause another battle (or Overrun). If

so, execute that battle immediately and resolve its consequences.

The retreating blocks are the attacker for this new battle. If the

retreating force enters an existing battle, the retreating blocks are

added to the forces in conflict. It is possible for a retreating force

to join a besieged force inside a castle and exceed, until the next

time combat is declared, the stacking limit of the castle (see 8.9.6).

This would in effect change the siege into a battle.

8.9 Siege Combat

8.9.1 Sieges in General

When combat occurs in a location with a castle, it is possible that

one side will choose to remain inside the castle. If so, the combat

becomes a siege. For a force to remain inside the castle, it must own

the castle, and it must be two blocks or fewer. (Disks do not count

toward this limit.) The side that owns the castle is the side that had

unit(s) in the location first (before combat broke out).

8.9.2 Declaring Blocks Inside or Outside

Blocks can be inside or outside of the castle. The number of blocks

that can fit inside a castle is limited to two. When combat is designated,

and not before, the side that owns the castle may choose

whether to be inside or outside of the castle. If outside—a battle

occurs; if inside—a siege. A force consisting of more than two blocks

must always choose to be outside. No blocks can remain inside if

some blocks are left outside. A force may elect to fight outside the

castle even if in a previous phase it elected to remain inside.

If the active player owns the castle and chooses to remain inside,

then no battle or Siege Combat occurs in this location this phase.

8.9.3 Disks

Disks are always considered inside the castle, regardless of the

disposition of the blocks. Disks do not count against the two block

castle limit. Disks are units that can be destroyed like a block, but

cannot move or fight. Only the results of a siege can affect the disk,

never a battle.

8.9.4 Siege Combat Procedure

The attacking player holds the Initiative throughout the siege and

there is no limit on the number of blocks the attacking player may

deploy. The defending player plays no cards during a siege nor

does he deploy any blocks. Follow this procedure for each Siege

Combat:

A. The attacker deploys (8.2.3) as many blocks as he wishes.

B. When the attacker is finished, damage is inflicted on the defending

force. No damage is inflicted on the attacking force in

a siege. One defending block or disk is lost for every 7 points

of Impact (the attacker may deliver less than 7 points of Impact

in a siege, but the defender will not be harmed.)

C. The defender chooses which block(s) or disk to lose. The identity

of those is made public.

D. If all blocks and disks inside the castle are destroyed, the castle

falls and now belongs to the attacking force.

E. If all the defender's blocks and disk are not removed, then both

sides' blocks co-exist in the location. When this happens, the

side that owns the castle is considered besieged (8.9.6). The side

that does not own the castle must declare combat at that location

during every Combat Phase the co-existence continues.

F. The defending player then draws one card for every block (but

not disc) lost (8.10).

8.9.5 Siege Combat Restrictions

Siege Combat has the following restrictions:

-

No gun or cavalry Special Attacks may be counted.

-

Loyalty Challenge cards cannot be played by either side.

8.9.6 Besieged Blocks

Besieged blocks may not be moved out of the location containing

the castle. Blocks that are part of a besieging force may freely move

away from the site of the siege during their Movement Phase.

If other blocks enter the location containing friendly besieged

blocks then all blocks are counted in the battle. Any battle that

occurs in any location automatically includes all blocks in that

location, regardless of the presence of a castle.

8.10 Card Replenishment

Card replenishment occurs immediately after a battle, siege or Overrun

is resolved (after losses and retreats but before any follow-on

battles generated by those retreats). After each battle or siege both

sides discard all cards they played during the combat and draw back

an equal number from their draw pile. Both sides also draw after a

battle, an additional card for every two blocks lost (round fractions

down). After a siege, the defending player draws one card for every

block lost. A card is not drawn for losing a disk.

Historical Notes

Appearing like dew,

vanishing like dew—

such is my life.

Even Naniwa’s splendor

is a dream within a dream.

Death poem of Toyotomi Hideyoshi

The story of Sekigahara begins with the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

In perhaps the greatest career in Japanese history, he had risen

through a feudal system from the bottom of society to its very peak.

Born a soldier’s son, he made himself taikō, supreme warlord and

ruler of all Japan.

In 1598, at the age of 62, he was overtaken by illness. His heir was

a boy of 5 years, hastily declared an adult and anointed the new

taikō. Before Toyotomi died he gathered the most powerful men

in Japan into two committees, balancing the power of each against

all others. Oaths were sworn to uphold the boy’s claim, and to leave

undisturbed the balance of power upon which he depended. With

these bare means, the best that could be constructed on short notice,

did Toyotomi hope to secure the youth’s passage to maturity.

In fact it took only two years for the tensions in this system to break

into open war. By the summer of 1600, two armies were rallied and

hurled towards each other, and the victorious Tokugawa Ieyasu

became Japan’s new master.

It had taken decades of warfare for Toyotomi and his predecessor

Oda Nobunaga to subjugate Japan’s belligerent fiefdoms. Their

prize was usurped in a campaign that lasted only seven weeks.

Tokugawa’s shogunate would rule Japan in peace for 15 generations,

268 years.

Ten years before the battle of Sekigahara, Japan’s present and future

lords stood together on a hilltop along the eastern coast. Toyotomi

Hideyoshi, at the zenith of his power and abilities, met with

Tokugawa Ieyasu, who had become his lieutenant. Once comrades

under Oda Nobunaga, then enemies in battle, they were now allies,

united in victory over the Hōjō clan. Here on the hilltop, Toyotomi

offered to Tokugawa a fateful proposition. In exchange for the 5

central provinces that Tokugawa’s family had known for generations,

he offered 8 provinces eastward in Kanto, further from the

capital, uncultivated, and surrounded by unfamiliar enemies. It was

a daunting proposition, but Ieyasu accepted on the spot.

The day Tokugawa arrived in his new capital of Edo is still celebrated

in that city, modern Tokyo. In 1590 it was a backwater, a

haggard castle rising from a swamp. But Ieyasu was more than a

warlord, he was an administrator of genius. From this damp village

in the Kanto he built an economic empire in the course of a single

decade. Ten years later, his annual income (2.5 million koku, manyears

of rice) was more than double that of any other daimyo.

Toyotomi had meant to consign Tokugawa to years of fruitless

difficulties, while alienating him from the politics of the capital in

Kyoto. Instead, by giving Ieyasu a large and fertile fief he allowed

the emergence of a natural successor, a first among equals, in the

ranks of leading daimyo. After Hideyoshi died, eyes shifted to one

man; behind the system of fealty, Japan had a dominant power

waiting to emerge.

***

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was one of the most remarkable men in the

history of Japan. He rose through the ranks in the service of the

greatest warrior of his day, Oda Nobunaga. Ugly and low-born, he

was called ‘monkey’ by his detractors. But his talent was extraordinary.

He came to be Oda’s most trusted retainer, pairing a series of

brilliant military successes with careful reassurances of complete

loyalty. One story still told today recalls Toyotomi warming Oda’s

sandals by keeping them against his chest. Toyotomi was always

careful to ask Oda’s direction in military matters, regardless how

unnecessary. And Oda delighted in Toyotomi’s prowess. Once,

seeing Toyotomi’s magnificent army, he remarked “His monkey

face has not changed, but who would dare call him monkey now?

Astonishing, indeed, is the way men’s positions alter.”

Toyotomi was a man of fine taste, but he could also explode into

rage at a slight. His elegant death poem, above, is one of the best

in the tradition. But bold indeed was the man who invited him

to tea in a cherry garden only to strip every blossom off the trees.

Ready to kill for such an insult, Toyotomi burst into the building

and saw a single cup of water in which was balanced one utterly

perfect blossom. Fury turned to gratification.

Rage like this could have geopolitical consequences. After fighting

a campaign in Korea, Toyotomi received a Chinese emissary

expecting to be named emperor of all lands. When instead he was

acknowledged ruler of only Japan, he exploded and launched a

second war. It was also this anger, or perhaps a general deterioration

of faculties, that inspired the killing of his own family. When

his preferred heir reached the age of two, Hideyoshi ordered the

death of his previous (adopted) heir, plus 29 of his family members.

By so doing he left his dynasty in the hands of a single 2-year-old

boy, completely vulnerable to disease or intrigues.

It was Toyotomi’s love of tea that launched his friendship with Ishida

Mitsunari. Mitsunari became Inspector-General in Hideyoshi’s

army, but he was not a military man; he was a tea master. Hideyoshi

knew from personal reflection that someone tasteful enough to

perform a superlative tea ceremony had talents that could be turned

to other tasks. To him, rank and birth meant nothing; only talent

mattered. In Ishida he found talent, and he promoted it. Ishida did

indeed have other abilities. He became a skillful administrator, and

in time, a relentless intriguer.

Ishida is the man who would later lead an army to defend the

Toyotomi heir. In the Korean campaign, Ishida made friends and

enemies that would shape alliances at Sekigahara. He once attended

a tea ceremony with daimyo Ōtani Yoshitsugu. Ōtani, who was

ill, left a drop of pus in the cup before passing it onwards. Other

participants were revolted as the cup reached their hands and they

were obliged to drink. To spare the man his agony, Ishida claimed

the cup out of order, drank everything in it, and apologized to all for

being so ‘thirsty’. Ōtani was astonished and grateful, and years later

would fight at Ishida’s side at Sekigahara. The opposite outcome

obtained when Ishida visited Kuroda Yoshitaka in Korea. Kuroda

was engaged in a game of go, and made Ishida wait. Incensed,

Ishida reported to Toyotomi that Kuroda cared more for go than

war. Kuroda was stung and never forgave the slight; in 1600 he

would be Ishida’s enemy.

Toyotomi was a man of such talent and character that he could

inspire loyalty through bold gesture. Many times in his career he

converted a deadly rival into a vassal through an act of disarming

courage or honesty. When asking his enemy Date Masamune to

submit, he revealed to Masamune the tactics he would employ

were they to fight, all while standing defenseless, having placed

his sword in his enemy’s hands. Date was amazed, and surrendered

his lands.

Bolder still, Toyotomi once travelled deep into Uesugi territory

undefended, to meet in person with his enemy Uesugi Kagekatsu.

Astonished by his courage, the Uesugi chose to become allies rather

than enemies.

What other men would have fought for, Toyotomi was given on

account of the strength of his character. To describe the heroic

impression Toyotomi made on his peers, historian Walter Dening

makes apt reference to a story about Hercules:

“O, Iole, how did you know that Hercules was a god?” “Because,”

answered Iole, “I was content the moment my eyes fell upon him.

When I beheld Theseus I desired that I might see him offer battle,

or at least guide his horses in the chariot-race. But Hercules did

not wait for a contest; he conquered whether he stood, walked, or

sat, or whatever thing he did.”

Having once trapped the rival Mōri clan in a siege, news came

to Toyotomi that his lord and mentor, Oda Nobunaga, had been

murdered by one of his own supporters. Toyotomi wanted to rush

to the scene, but a departure would leave him vulnerable to attack.

Toyotomi presented himself to the Mōri and explained the situation.

His courage spoke volumes, as did his indifference. Against

so bold a commander, the Mōri preferred to decline combat as his

troops left the scene.

That moment was the greatest turning point in his career. Returning

to the site of treachery, he found and defeated the disloyal forces.

He had avenged the betrayal, and his recent successes made him

the preeminent warrior in Japan. It was he around whom the Oda

power structure now consolidated—even Oda’s son was happy to

follow Toyotomi. He had completed his rise; he was taikō.

Tokugawa Ieyasu, though of noble birth, rose from broken circumstances.

He was separated from his mother at age 2, kidnapped at

age 6, and taken as a hostage at age 9. Perhaps as a result of these

events, emotion played little part in his character. He made his

decisions on rational grounds, regardless the emotional toll. When

they were implicated in a treasonous plot, he ordered the death of

his own wife and first-born son.

Like Toyotomi he found it necessary to diminish himself before the

rulers of the day in order not to rouse their suspicions. He took great

pains not to reveal his talents or his ambitions, but some noticed all

the same. An old enemy, Takeda Shingen, noted “Ieyasu cherishes

great hopes for the future... He won’t eat anything out of season.”

Unlike Toyotomi, who made a virtue of his vulnerability, Ieyasu did

indeed act with the overcaution of one who ‘cherishes great hopes’.

When he travelled out of his fiefdom he made elaborate escape

plans should treachery occur.

Beneath the deprecation and caution was an extraordinary mind.

His generalship was superlative. Once when fighting the Takeda

he found himself threatened with disaster. Having lost a battle, he

retreated with only a few troops to a nearby castle, his enemies in

pursuit. On arrival, he ordered the gates flung wide, bright torches

burnt outside the entrance, and a loud drum banged throughout

the night. When the Takeda forces arrived, they surmised Ieyasu

was planning an attack—rather than a desperate defense—and

declined to give battle.

Tokugawa served most of his life under the leadership of his two

great predecessors, Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Only

when these warlords died, having unified the nation but failed to

provide an heir, did Tokugawa reap the fruits of their labors. An old

story explains it thus: Oda Nobunaga makes rice cakes, Toyotomi

Hideyoshi cooks them, and Tokugawa Ieyasu eats them.

How much of Tokugawa’s success, then, was owing to good fortune?

Certainly he benefitted from circumstance. Several of his rivals died

at convenient moments: not merely Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi

Hideyoshi but also Takeda Shingen and Maeda Toshiie. But if his

path was fortunate, was there another who could have walked it?

Tokugawa needed generalship and diplomacy to expand his fiefdom;

uncommon self control, in order not to come into conflict with his

lords; and extraordinary management ability, that he could develop

his Kanto domain into the engine of war and commerce that it became.

Tokugawa played his hand so carefully, and showed such skill

in its execution, that it would be unfair not to award the majority

of the credit for his accomplishments to his own efforts.

***

After Toyotomi’s death, Japan emerged in stages from the rigid stasis

he had willed for it. Japanese troops were still in Korea, fighting

and losing the second of two successive wars. For a time, Toyotomi’s

death was concealed by the state. Once the troops returned and the

truth emerged, it was Tokugawa who offered the first test to the

new regime’s stability. He assigned a few of his family to political

marriages, something forbidden by the system Toyotomi had given

them. Fractures formed in the committees and sides were taken.

Then the actions of Toyotomi loyalist Ishida Mitsunari brought

the simmer to a boil.

First Ishida attempted to sow suspicion between the most powerful

daimyo, suggesting to Tokugawa that Maeda Toshiie would kill

him when given the chance. Soon after there was an attempt on

Tokugawa’s life. The attempt failed, Ishida was implicated, and a

group of Tokugawa supporters conspired to kill Ishida in return.

Cornered, Ishida fled to the mercy of his greatest enemy, Tokugawa

himself. Astonishingly, Tokugawa let him free and escorted him to

safety. The reasons for this action have been much guessed at over

the years, and several theories have been entertained. First, that

Tokugawa was naïve and thought Ishida a friend. This is highly

unlikely. Second, that he was prone to forgive. One of his favorite

sayings was Lao Tsu’s “Requite malice with kindness”. He had

dodged assassination once before, and had returned the captured

killer to his master, saying that anyone bold enough to creep into

his bedroom and perforate his bedding with a sword was undoubtedly

a “valuable man”. Third, and most likely, however, Tokugawa

protected Ishida because he saw in the latter an instigator capable

of unbalancing Toyotomi’s careful system. Political disequilibrium

would give Tokugawa his best chance to rule, and yet he could not

be seen to create it himself, lest others ally against him. As one advisor

put it, it was through men like Ishida that soon Ieyasu might

come to rule all of Japan.

Ishida’s close escape did not stop his campaign of intrigues. Instead,

he crafted a more ambitious plot to ignite war against Tokugawa

with the help of daimyo Uesugi Kagekatsu. The Uesugi lived in

the north of Japan, near to Tokugawa’s fief, so disobedience by

the former would be the latter’s to correct. Ishida arranged with

Uesugi that a disturbance would be created, and as Ieyasu went to

address it, an army of his enemies would be organized behind him.

Tokugawa would be surrounded and outnumbered.

The plot was launched in 1600, when Uesugi set about building

a new castle and engaging in conspicuous fortification. Tokugawa

asked that he come to the capital to explain his actions, and received

in reply an insulting rebuff. Citified samurai collect tea implements,

wrote Uesugi, while country samurai collect weapons. The gauntlet

was thrown, and Tokugawa had no choice but to respond.

Tokugawa gathered a force and departed Osaka castle. He headed

east and north on the Tōkaidō, one of Japan’s two highways. He

moved slowly, taking forty days to reach Edo, and listening all the

time to reports from friends in Osaka. What he heard was the rapid

unraveling of Toyotomi’s political equilibrium. A nation of warriors,

Japan demanded conflict and command. Toyotomi’s system,

of peace and divided power, was in fact a vacuum, and that vacuum

would now be filled. Almost instinctively, the nation resolved to

fight. There would be a war, and whether in Toyotomi’s name or

Tokugawa’s, Japan would have clear leadership.

It was a war born of a trap, and it sprang like a trap, catching even

the protagonists by surprise with the rapidity of events. What Ishida

had hoped would be an anti-Tokugawa action quickly became a

crucible for determining Japan’s entire structure of governance.

Would Japan be led by its strongest daimyo, Tokugawa Ieyasu,

or by a caretaker safeguarding the Toyotomi succession? Two

causes opposed each other, and two armies formed to champion

them. Tokugawa’s became known as the army of the East, Ishida

Mitsunari’s the army of the West.

Tokugawa launched a frenzied campaign of correspondence, inviting

daimyo to join him in the upcoming war. He wrote 180 letters,

to 108 lords throughout Japan. He asked for their allegiance, and

99 of them offered it. It is an irony that it would fall to Ieyasu, unemotional

and incapable of small talk, to win a war through letterwriting.

In his messages he said he would depart Edo on October

1st, but when that date arrived he could not yet move because he

was still uncertain who was with him. He remained until the 7th,

when he decided urgency was more essential than certainty.

Ishida Mitsunari gathered the western forces from his position in

the capital region. He and his supporters were able to personally

address most of the daimyo they wished to recruit. Mōri Terumoto,

one of Japan’s most powerful men, was narrowly persuaded to join

the western army. Another leading warlord, Kobayakawa Hideaki,

was on his way to join Tokugawa forces when he was waylaid and

talked into a change of allegiance.

As the war began, Ishida’s strategy was twofold. First, he sought

to consolidate the castles in the capital region under his control. A

number of sieges were launched, which when successful resulted

in solid control of the area. The sieges were slow, however. It took

eleven days to capture Fushimi castle in Kyoto. Tanabe castle took

even longer on account of the presence of a famous poet and his

valuable library—plus the indifference of the sieging troops, who

often ‘forgot’ to load their cannon with shot. The latter operation

took so long that the units involved were not available to fight at

Sekigahara.

Ishida’s second priority was to secure the western end of Japan’s

two highways. He made an alliance with Oda Hidenobu, grandson

of the warlord Oda Nobunaga, who controlled Gifu castle. All the

roads west of Gifu, on both highways, were controlled by western

forces.

At the same time, Ishida had to negotiate with Mōri Terumoto, the

strongest daimyo of his faction. Mōri’s income was second only to

the Tokugawa in all Japan, and his stature was such that he owed

loyalty not to Ishida but to the Toyotomi. As such he took actions

independently, uncoordinated with Ishida’s designs. He moved to

Osaka castle with 30,000 men and declared himself the guardian

of the Toyotomi family, heedless of Ishida’s need for those troops

in the field. Ishida might have coaxed Mōri into the conflict, had

he been willing to sacrifice some of his own stature. The failure of

these leaders to coordinate was to have enormous consequences in

the Sekigahara campaign.

Ishida gathered his army at Ogaki castle, just west of Gifu. Having

consolidated the capital region of Japan, he knew now that

Tokugawa would have to come to him.

As Tokugawa moved to Edo in the early days of the conflict, his

strategy was still extremely fluid. He intended at first to pursue the

northern campaign against the Uesugi, and moved his headquarters

north of Edo, to Oyama, in preparation. Then he changed his mind

and returned to Edo. He resolved upon a new strategy. Rather than

fight small battles around Japan, he would force a single decisive

battle that would resolve all other conflicts in one blow.

Fighting Uesugi was left to Date Masamune and other local daimyo.

Another Tokugawa ally, Maeda Toshinaga, might have been included

in the campaign had he not been engaged already against

regional enemies. Tokugawa turned all of his forces to the west.

The westward battle plan had three stages. First, a force would be

deployed to take Gifu castle and establish a forward base of operations.

Second, two armies would march from Edo to that gathering

point, one along each highway. Finally, the large army so assembled

would march westward for a climactic confrontation.

The assault of Gifu would enable Tokugawa control of the twin

highways of central Japan, the Tōkaidō and the Nakasendō, which

he would then use to rapidly deploy his forces westwards. Tokugawa

sent an army of 16,000 from Edo along the Tōkaidō, under daimyo

Fukushima Masanori. Fearing that force might be insufficient,

he sent another 18,000 to follow them. All reached Gifu, where

the plan almost fractured because the two commanders could not

resolve the honor of leading the attack. The night before they were

to begin the assault, they nearly fought a duel before a solution

was agreed: each would lead a separate attack on opposite sides

of the structure.

At the same time, the campaign against Uesugi Kagekatsu proceeded.

Eventually, Date and the Tokugawa allies were able to

overcome the Uesugi, in a battle that occurred after Sekigahara

but before word had reached the north.

With the highways under his control, Tokugawa Ieyasu moved to

deploy the rest of his army. In contrast to his slow departure from

Osaka, he returned with alacrity in order to surprise his enemies.

He sent 38,000 men under his son Hidetada along the Nakasendō,

and took 33,000 with himself along the Tōkaidō, meaning to unify

the forces at Gifu castle.

During the march Tokugawa continued to receive letters pledging

allegiances, in some cases from daimyo who, unsatisfied with their

first decision, were choosing sides for the second time. He noted

the fluidity of loyalty, worried for the reliability of his men, and

resolved to test the allegiance of his enemies.

Tokugawa’s Tōkaidō force completed the march successfully and

arrived at Gifu castle on October 19. The Nakasendō force was

delayed. Weather was partly to blame, but more importantly, Hidetada

took up a siege at castle Ueda against the instructions of his

father. The siege drew on under the cunning defense of local daimyo

Sanada Masayuki, until Hidetada eventually abandoned it. By then

he was hopelessly late, and when the battle of Sekigahara broke out

he and his 38,000 men were still 200 kilometers away.

When they first spied the eastern army, Ishida’s western forces

were camped at Ogaki castle, west of Gifu. Tokugawa set his camp

5 kilometers to their northeast. Ishida’s western force numbered

82,000, Tokugawa’s eastern army 89,000. Though of roughly equal

size, the two forces were in very different psychological states.

The western army was closer to home and more rested. Supply

lines were cleaner, reinforcements closer. They camped not far from

Ishida’s home castle at Sawayama. But the early arrival of eastern

troops had unnerved them. Clearly, their plan to distract Tokugawa

in the north had failed. Further, the eastern army was larger than

expected—Ishida had underestimated the degree of support there

would be for Tokugawa. Finally, since this territory was home to

the western forces, Ishida had more to lose by fighting here. He

had to be concerned about defending Osaka, Kyoto, and Sawayama

from invasion. While Tokugawa might be at liberty to give or refuse

battle, Ishida felt his options narrowing.

Tokugawa put his proximity and confidence to immediate use

by attempting to arrange defections among the western forces. Ii

Naomasa and Honda Tadakatsu, some of Tokugawa’s most loyal

leaders, were dispatched to speak with the retainers of several western

daimyo. To Kobayakawa Hideaki they offered a domain of two

provinces, if he were to switch sides and fight for Tokugawa. The

price was agreed, and the seeds of treachery planted.

The betrayal of Kobayakawa had its roots in an old grudge against

Ishida. The former, after leading Japanese forces in Korea in what

some considered a reckless manner, was stripped of much of his

territory by Toyotomi. He suspected truth in the rumor that Ishida

had recommended the action. Though the land was later returned,

Kobayakawa’s resentment persisted.

After reaching proximity with the enemy, eastern leadership considered

several strategic options. Ii Naomasa proposed an attack

on Ogaki castle, creating at once that definitive battle for which

the army had been gathered. Honda Tadakatsu preferred a march

to Osaka, which if unopposed would end the war just as decisively.

Tokugawa’s final decision was to mask Ogaki castle with a small

detachment of troops while marching west towards Sawayama and

then Osaka. If successful, the western forces would be cut off from

the ground they sought to defend.

The western army was also unsure of strategy. Notified that

Tokugawa planned to bypass his position, Ishida scrambled for a

proactive plan. A night attack was proposed, only to be rejected

because Ishida felt it suitable only for a weak or desperate army.

Instead, he settled on a night march, to select and occupy ground

for a battle in the morning. For the site of that battle, he chose the

crossroads of Sekigahara.

Drenching rain pelted the western troops as in darkness they departed

their camp. They marched westward to a fork in the road

offering different routes to Kyoto and Sawayama. To defend both,

a stand would have to be made at Sekigahara. Hills ringed the road,

and between them there would be room for battle. Ishida’s men took

the high ground all around the site and waited for dawn.

Tokugawa’s night was nearly as restless. At 2:00, despite the storm,

he mounted his horse to reconnoiter the ground ahead. When he

was satisfied with the approach, he woke the army and brought them

on behind him to the site of battle. He arranged his men along the

road, the hills having been occupied, with a substantial force to the

rear to prevent encirclement and facilitate escape. Both commanders,

in fact, were careful to ensure an escape route – Ishida stationed

himself at the back near the road that led to Sawayama.

Both sides pressed for combat despite having substantial temporary

weaknesses. Ishida had twice tried to summon the 30,000 Mōri

troops at Osaka castle, and they had not yet come. The siege of

Tanabe castle had just finished, and another 15,000 troops were

on their way to join the main force. Tokugawa’s son Hidetada was

late with 38,000 men a few days march to the northeast on the

Nakasendō. Still, each felt they had more to fear from delay than

action. Ishida worried about the integrity of his coalition and knew

that to retreat further would be to sacrifice his home of Sawayama.

Tokugawa held the advantage of surprise against an enemy with

more local resources.

Each army was made up mostly of ground troops, armed with

spears and swords. Each had some cavalry and some arquebusiers.

The arquebus had been revolutionizing Japanese warfare in the

half-century since its introduction, in the process making archery

obsolete.

The morning of October 21, 1600 was muddy from a night of rain,

and hazy with mist. The army of the East launched the battle when

Ii Naomasa’s troops, called the “Red Devils” for the fearsome red

lacquered armor they wore, charged the field. Fukushima Masanori,

who had been promised the honor of first attack, plunged forward

immediately as well, assaulting the strong central position of the

stalwart loyalist Ukita Hideie.

Ishida ordered a counterattack, and to his dismay found that some

of his units refused to move. The Shimazu merely held their positions,

not fighting until they were attacked. On the flank, Kikkawa

Hiroie refused a signal to attack, and the 15,000 Mōri troops behind

him were satisfied to wait. Repeated orders were also sent to

Kobayakawa Hideaki demanding an attack, but he stood on the

southern hillside as battle raged in the valley.

Tokugawa, too, was asking Kobayakawa to move. Finally, shots

were fired in his direction, in demand of a decision. With that

signal, Kobayakawa engaged, charging down the hillside to attack

his former allies. The southern end of Ishida’s line was enveloped.

All across the field, western forces were being beaten back, despite

the valor of a few loyalists.

The eastern army began the consolidation of its victory. Tokugawa

Ieyasu erected a court on the battlefield in which to receive commanders

and the heads of his enemies. To loyal friends like Fukushima,

Ii and Honda, he declared his everlasting gratitude. He

praised the turncoat Kobayakawa and allowed him to lead an attack

of Sawayama castle (now largely a formality). He reserved his greatest

scorn for those who had refused battle, specifically the Mōri.

Ishida escaped into the mountains, to be caught a few days later

and executed. Ukita, a young daimyo who had fought tenaciously,

was forgiven his involvement but forced to live in exile and abstain

from politics. Toyotomi Hideyori was entrusted to Tokugawa’s care,

and survived another 15 years before being killed for disloyalty.

The Mōri were stripped of most of their land and wealth, leaving

them bitter and vengeful for centuries to come. Their children

slept with feet pointed east, in insult to the victors of Sekigahara.

It became a tradition, in Chosho where the Mōri lived, to open

each new year with a ceremonial exchange in which prominent

leaders would ask of the daimyo “Has the time come to begin the

subjugation of the [Tokugawa]?” to which he would reply “No, the

time had not yet come.” (More than 250 years later the time finally

had come, and the rebellion that overturned the shogunate was led

in part by Chosho.)

The Sekigahara campaign was fought rapidly. In seven weeks of

hostilities, the fate of Japan was settled. The whole episode, including

Tokugawa’s march northwards and letter-writing campaign, took

just over three months. In that time, every daimyo had to select

a side, raise troops, deploy and fight. Little wonder, then, that the

campaign was so unpredictable, loyalty so fluid, plans and objectives

so often revised. It was an improvised war.

In this brief and unstructured engagement, loyalty was as important

as troop strength. Victory went not to the largest army, but to that

which best supported its commander.

Tokugawa returned victorious to Osaka castle exactly 100 days after

he had left to punish the Uesugi. His dynasty would last 268 years.

It is remarkable that equilibrium so durable could have arisen from

an episode so unstructured and chaotic. But it was not by chance

—after he subdued his enemies, Tokugawa took every measure to

subdue the nation.

After Sekigahara, Tokugawa spent the last 15 years of his life

laying the foundations for the Tokugawa shogunate. (The title

of shogun, inaccessible to Toyotomi for reasons of low birth, was

accorded to Tokugawa.) He transferred the title to his son years

before he died in order to ensure a good succession. He invented

a new social hierarchy and lived to oversee it. To every station in

society he gave responsibilities and obligations. To the samurai, he

gave the duty of martial ceremony, in lieu of martial acts. He set

the nation busy complying with new objectives, and thus weaned

them from violent impulse.

Tokugawa did what Toyotomi could not: domesticate a nation of

warriors. Under Toyotomi, for sake of war, conquest of Japan was

followed by invasion of Korea. Tokugawa instead made warriors into

governors and citizens. Tokugawa rule was known as the bakufu,

which means ‘government from a tent’, or governance by soldiers.

In the strict class hierarchy of the Tokugawa period, samurai abandoned

bloodshed and became members of the governing class.

In this transformation we see the magnitude of Tokugawa’s accomplishment.

Just as he had throughout his life controlled his

own emotions, now he controlled those of a nation. A great administrator,

he created the institutions that turned an entire people

from war to peace, ending an era of chaos and launching an era of

tranquility. The Buddha said “One who conquers himself is greater

than another who conquers a thousand times a thousand on the

battlefield.” Tokugawa Ieyasu did not himself subdue the various

territories of Japan, as did his predecessors. He was fortunate to inherit

the fruits of their struggles for unification. But only Tokugawa

conquered the people, because of the three great warlords, only he

had first conquered himself.

Design Notes

Sekigahara is an unusual game. The peculiarities of the design are the

product of two priorities: that it depict the conflict in its mechanisms

rather than merely in its particularities, and that it adheres to certain

design objectives that I consider important.

I prefer a game that rewards skillful play and diminishes the effect

of chance. One of my earliest and easiest decisions was to exclude

dice from the design. A die roll generates a two-sided surprise: both

parties are unable to predict the result of a die roll, and thus cannot

plan for it. I prefer one-sided uncertainty (hidden units and cards)

to encourage planning and bluffing.

For playability, I wanted the game to finish in 2-3 hours. This naturally

set a limit on the amount of complexity I could introduce into

the rules. Fortunately, as I will explain below, I prioritized realism

over complexity, and found I could accommodate quite a lot of the

former despite a cap on the latter.

There exist in wargaming a series of game types: card-driven, block,

counter. For each of these categories the seasoned gamer will immediately

recall a series of games, some classics and some best forgotten,

which fit the mold. There have even developed conventions

within conventions, such that we can expect a card-driven wargame

to offer a tradeoff between action points and events, and a block

game to feature step-losses and lots of dice. What this conventionality

gains in familiarity it loses in realism. Can the same mechanism

accurately convey different conflicts centuries apart? Some would

say it can, so long as you adjust the incidental elements in the game:

unit values, events, map, ‘chrome’ rules to add color. I began with

the assumption that this would not suffice. Rather than convey the

spirit of the conflict through incidentals, I attempted to convey it

through the design mechanisms themselves.

One could also debate what constitutes the spirit of the conflict,

and what it means to be accurate in design. Wargames usually

achieve accuracy through weight. We forgive a game complexity

if it provides greater realism. But what kind of realism is best? It

may seem realistic to list precisely the fighting value of every unit,

or draw from a deck of historical events, but the commanders in

the war were never privy to such knowledge. Make the game too

‘accurate’ in these regards and you degrade the accuracy of the experience.

Fidelity must be declared to realism of ‘details’ or realism

of experience; this design has favored the latter.

I sought to convey the experience of being a commander in the war

of Sekigahara through the mechanisms of the game. Since the war

was characterized by uncertainty—the fog of war so close leaders

could choke on it—so should be the mechanisms (hidden blocks

and cards). Since the war was won and lost over loyalty, a major

mechanism (the cards) was introduced to depict loyalty. Mechanisms

were determined not by wargaming convention, but by the

peculiarities of the Sekigahara conflict.

The war of Sekigahara was unusual in several ways. First, the extreme

importance of loyalty and personal legitimacy. Second, the haste and

uncertainty under which it was organized and prosecuted. Third,

the absolute centrality of people, and thus the importance of their

personalities and their safety. Finally, the way honor and the pursuit

of honor dominated behavior throughout the conflict.

No factor was more important in determining the outcome of the

war than loyalty. Neither commander could be certain of his supporters,

nor entirely confident in numerical superiority. Battles were

won instead by loyalty and legitimacy. Some troops fought heroically

(like Ii and Ukita), some were passive (Mōri), some treacherous

(Kobayakawa). The final battle, indeed the entire war, was decided

by defections and disloyalty. To model loyalty I introduced the

deck of cards, representing the support of the troops. The bigger

the hand size, the more legitimacy. The possibility was introduced

of a unit brought to battle and then refusing to take part (a typical

occurrence in this war). In order to model treachery, I added ‘Loyalty

Challenge’ cards, which have the additional benefit of making each

battle a tactical exercise of bluff and deceit. Tokugawa has one more

of these cards than Ishida, and the difference may be telling.

Sekigahara was an improvised war. It was a civil war based on people

and not geography, in which over 100 daimyo separately made allegiance

decisions. Fighting lasted just seven weeks, with another

seven of preparation. The struggle began and finished with forces

scattered across Japan, fighting local enemies and capturing local

targets. Despite this chaos, Sekigahara was a strategic conflict. It

emerged out of a well-planned trap, and ended in a well-planned

strategic attack. Chaos swept around the feet of our protagonists,

but it did not overwhelm them. I have modeled this uncertainty

with a semi-randomized unit setup that forces each player to open

the game with improvisation, even as other factors (compounding

special attacks, card carryovers across turns, bonuses for castle and

supply control) urgently encourage them to form a strategy. To depict

the tension between opportunism and centralization the board

is littered with easy targets but players begin with precious little

organizational capacity (just 5 cards). A few factors are known to

each player; the rest is a blur of uncertainty. Blocks are hidden, cards

are secret and rapidly recycled, reinforcements drawn at random.

Extreme as this may seem, if I have erred it is on the side of overcertainty.

No mechanism in the game can reproduce the dismay

of the western army on the arrival of Tokugawa at Gifu castle, far

sooner, and with far more troops, than expected. I happily sacrifice

perceived detail to recapture the authentic feeling of improvisation

and uncertainty felt by the leaders in this war.

There are three figures whose death or capture would have transformed

the conflict. Tokugawa and Ishida, of course, and also

Toyotomi Hideyori. Personality drove the war in a more subtle way

as well. Tokugawa’s stronger personality allowed better coordination

of his daimyo. Ishida’s conspiratorial talents helped him set the

initial trap with Uesugi Kagekatsu, but his tense relationship with

Mōri Terumoto may have cost him the war. Given the importance

of people and personality, it was essential that players represent

protagonists and not causes. (Thus the game ends on protagonist

death or capture.) The Ishida-Mōri relationship, in which personal

interest took precedence over loyalty to their cause, required an

additional mechanism to depict the tradeoff Ishida faced between

strength and primacy.

Honor was the most nonintuitive of the themes that defined the

conflict. Honor drove daimyo to besiege castles that were of little

strategic importance. Honor caused breakdowns in coordination

amongst allies. Honor is why Torii Mototada’s doomed defense of

Fushimi Castle is still celebrated in the present day. Honor nearly

disrupted the assault on Gifu castle, when two Tokugawa daimyo

proposed to fight each other (for the right of first attack) before they

faced the enemy. Honor led one earlier Tokugawa enemy to burn

incense in his helmet before a battle so that his head would make

a better trophy. (Tokugawa was so impressed he recommended the

practice to his own followers.) How to model a factor that could

create—even celebrate—martial failure in the name of a higher

cause? I settled on two mechanisms, both regarding the dispersion

of cards. First, bonus cards are allocated according to losses in battle,

not victory, with extra cards given to those dying in defense of a

castle. Second, the owner of more castles draws an additional card

at the beginning of each week.

The units that fought in the war were characterized above all by

their clan. A secondary characteristic was the use of guns or horses.

Cavalry did not travel faster than ground units because they were

accompanied by non-mounted retainers. The secondary purpose

of the special units in the game was to reward central organization.

Armies that took time to organize became more powerful, as

depicted by the compounding special attack bonuses.

Many clans fought in the war and for game purposes I had to select

just a few. In Ishida’s case it was simple—Mōri, Ukita, Uesugi, and

Kobayakawa were the strongest and most important daimyo in

the western coalition. Tokugawa had a wider range of mid-sized

supporters, and I chose them based on regional representation and

centrality to the plot. Other worthy names were consolidated under

my selections: Fukushima was supported by Ikeda Terumasa, Date

by Mogami Yoshiaki. Maeda is included for geographical balance

and because it was one of Japan’s strongest houses, though its impact

in the Sekigahara campaign was primarily regional.

Japan was dotted in castles and I include only a few of them in the

game. Gifu, Ueda, and Osaka are essential to tell the story; the others

were selected representationally, generally in places where sieges

occurred. Resource areas are meant to depict control of territory,

and so I have scattered them across the map. I have also tried to

convey the importance of the Tōkaidō and Nakasendō highways.

In a campaign characterized by dispersed forces and targets, the use

of good roads to centralize and coordinate was essential. Not every

little road could be included on the map, of course, and because

there are always more, I have written the retreat rules to prevent

easy encirclements.

The ability to build riskier or safer armies and to groom your hand

of cards in order to motivate them is one of my favorite elements of

the design. The most powerful army in the game is one of uniform

type—many blocks from the same clan, or many special attacks of

the same variety. This is also the most difficult army to field, as it

takes careful card preparation and a well-timed attack. The double

attack cards are essential for this purpose, and are more valuable than

they first appear. I also enjoy the tension in sequential deployments

of blocks during a battle. Some are at risk of defection (those for

which no more cards are available) and some are not. Players can

be cautious or reckless in their battlefield decisions. There is a thrill

in deploying a potential defector successfully and an even greater

one when you turn an enemy unit to your side.

Elegance was always a priority. One reason for the unusual block

shape is that they can be stacked and thus every army viewed at

once, without flipping or rearranging the pieces. Where the characteristics

of the conflict did not dictate complexity, I made every

effort to reduce it in the game. In the words of Einstein, a game

should be as simple as possible, and no simpler.

—Matt Calkins